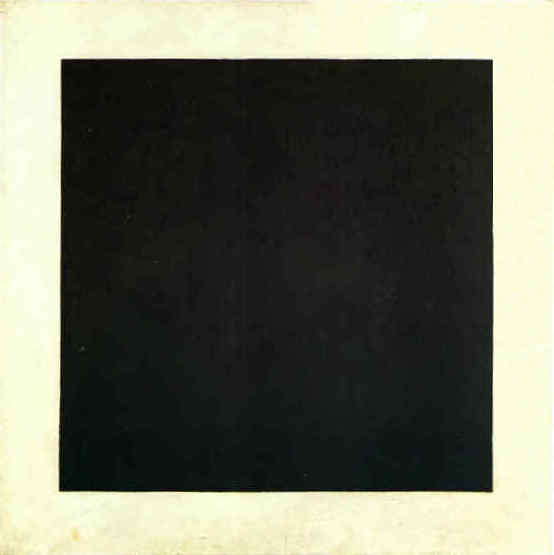

“Black Square” by Kasimir Malevich. What happens when the artist refuses compromise?

I’ve known a fair number of so-called “creative” people in my time — I consider myself one of them — and there is one thing that we all seem to have in common: we’re always reaching, unsuccessfully, for control.

At a glance, this might seem counter-intuitive: we think of the “artist” as a free-thinking, free-wheeling catapult of ideas, tossing concept and execution into the void and never thinking twice about where and how and on whom they land.

The reality, of course, couldn’t be further from the truth.

When a major-league pitcher throws the baseball, he knows that the moment the little round bundle rolls off his fingertips, it’s gone: no amount of gut-muscle-clenching or back-tooth-grinding is going to have the slightest effect on the ball’s trajectory. At the same time, however, his mind is churning, racing ahead to the next pitch, the next hitter, the next set of conditions, continuing play into a million hypothetical futures. When an actor delivers a line, or an artist hangs a picture, or a playwright lurks outside the preview performance of his (or her) masterpiece, she (or he) is seeing the work continue through time and space from the moment lips or brush or eye released it. The creative skills that allow the artist to produce his work in the first place also condemn him to watch it evolve eternally back and forth in time, endless variations, echoing forever.

“Should I have …?”

“Oh, shit! Why didn’t I …?”

“Next time I’m going to … “

The ability to model possible futures is a quality that almost every human being possesses, to some degree or another. When we consider dropping a hammer from the top of a ladder onto the balding head of a brother-in-law in a blue coverall working seven feet below, we can foresee an array of consequences to that act, some positive (depending on our point of view), some negative. We will usually find it unnecessary to actually drop the hammer, having worked out so many of the possible futures already, in a split second, that the physical act is rendered superfluous.

Pablo Picasso once observed that the only perfect picture is a blank canvas: once the first mark is laid down, the second-guessing begins — once the journey is well and truly begun, the artist must face the fact that he has no map and no guarantee that the road won’t take him right over a cliff just around the next bend.

Sometimes this ability to see the unfolding of events is absolutely essential to the creative process: an engineer who designs a bridge that collapses six months after completion is going to be seen as either a failure or a psychopath. At the same time, however, there has to be a decision-point, at which the available choices collapse into a single path: the actor who can’t deliver a speech without first trying to anticipate — laboriously, line by line — all the possible reactions the audience might experience is going to end up provoking no coherent reaction at all. The artist who will grab his audience and hold it is the one who makes his decisions and runs with them, fully committed, leaving the audience to ride along or fall by the wayside according to its own inclinations.

Inevitably, this can lead to a couple of problems.

The first is the “Plan B” question: If you have assessed a million possibilities and chosen the one you believe is going to be the only right one, then falling back to second- or third-choice alternatives — for whatever reason — is just not acceptable. You’ve already been there, you’ve played through all those other options and you’ve made the only correct choice. It’s unreasonable to retreat to a less-suitable plan just because the boss’s contact lenses are defective and he can’t get comfortable with vertical lines, or the bride got a sunburn yesterday and no longer wants blush-pink roses in her bouquet, or the prima ballerina feels bloated today and is not entirely confident in the upper-body strength of her partner in the pas-de-deux.

Which leads us to the second problem: Artists often have trouble working with others. When we perform our creative function, whatever it may be, we find it difficult to relinquish control of the work to someone else for modification or refinement. Even in those areas in which the team is paramount, such as theater, or team sports, or a symphony orchestra, we’re still operating as fully independent parts of a larger machine: one cogwheel does not change its shape to accommodate the others; the parts are designed and fitted into place according to their inherent suitability, with the structural integrity and solidity of each individual component essential to the smooth running of the whole device. If the first violin in a performance of a Mahler symphony suddenly decides that the second trombone is just not carrying his weight, it doesn’t help for her to start improvising ways to compensate.

The Surrealists of the 1920’s and 1930’s believed that every human being was an artist, under the skin; that the only thing that separated the writer or poet or painter from everyone else was the actual act of diving in and doing the thing, damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead. At the same time, however, it should be noted that these were men (mostly) who wore suits, ties, hats and nice shoes in public; who ate in the appropriate restaurants and were extremely uncomfortable with women and homosexuals. Rebellion, for the Surrealists, had some well-defined limits.

All of which leaves many of us in an awkward — and sometimes anti-social — position with regard to the society for whose benefit we like to believe we’re working. If we’re not convinced that we’re right, then we can’t perform our function properly, but if we do believe we’re right, then we can’t adapt to the whims and desires of the people who, for better or for worse, make the final decisions about our viability as artists: the critics, the conductors, the managers, the people who sign the checks.

Is there a solution? I doubt it, but more importantly, I don’t think we should ever want one. I believe that the fundamental conflict between individual excellence and cooperative achievement is the engine that keeps human society afloat, that provides the energy to identify and solve problems. The artist risks personal failure should he commit to the wrong choices, while society, in its turn, is forced to accommodate the snarky, the tormented, the overconfident, the childish; the Steve Jobs, the Jackson Pollocks, the Tycho Brahes, the William Shakespeares.

Between the two poles, greatness can happen: the grain of sand caught under an oyster’s shell may be intensely irritating to the poor oyster, but it will endure, and that temporary discomfort will, one day, produce nothing less than a pearl.

* * *

Brilliant, astute and right on the money!