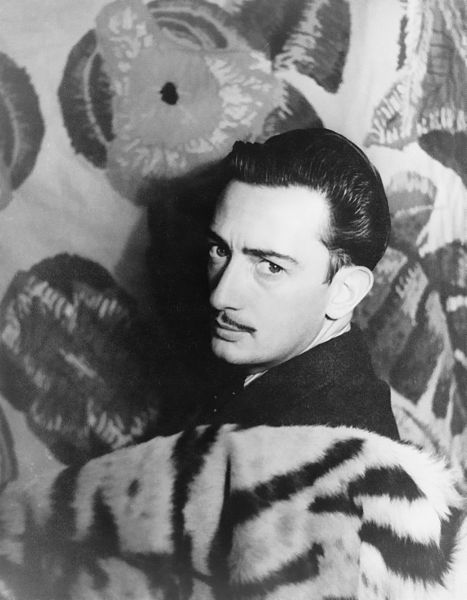

Portrait of the artist as a young moustache. As his career took off, his personal grooming took over.

Today, May 11, is the anniversary of the birth of painter Salvador Domènec Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquis de Púbol — better known to most of us as Salvador Dalí. Had he lived, he would be 108 years old today, an accomplishment that he might have celebrated in some way involving camels, scuba gear, an IBM Selectric typewriter, and oregano.

When you mention Surrealism (with a capital “S”) in most company, Dalí is almost always the first (sometimes the only) name which comes to mind. This is unfortunate, since he was never a very good Surrealist: the movement had strict guidelines and theoretical underpinnings that he ignored, violated or corrupted whenever it suited him. What Salvador Dalí was good at was self-promotion; he was his own masterpiece, and the fashionable art movement of the day was just one of his tools.

The artist as artifact is not a new idea: Baroque composer Antonio Vivaldi — nicknamed “The Red Priest” — was, at one time, so much in demand as a music teacher that parents would pretend to abandon their children so that the kids could apply to study in the music school for orphans at which Vivaldi was an instructor. The violinist Niccolò Paganini was adored to such a degree that women attending his concerts would faint during the cadenzas. At the beginning of the nineteenth century Lord Byron was better known for his hair, his debts, and his ambiguous sexuality, than for his writing.

It was the twentieth century, however, that brought access to ever-larger audiences — first through radio, then television, now the internet — providing artists with greater scope for aggrandizement than ever before. Individuals such as Jean Cocteau and Gertrude Stein became professional celebrities, parlaying moderate personal artistic or literary ability into a visibility often greater than that of the more talented artists, musicians, filmmakers and writers who surrounded them. Andy Warhol made no secret of his hunger for fame; the recently deceased Thomas Kincade created a highly successful brand out of a limited technical ability and an unabashedly hackneyed and sentimental narrative content. Englishman Damien Hirst often describes himself as an “entrepreneur”, rather than an artist, creating works of questionable artistic merit designed specifically to generate frenzied media attention.

Salvador Dali drifted away — or was driven — from the Surrealist clubhouse over time, gradually moving to overtly religious themes in his later career, becoming more the heir of El Greco than of de Chirico. Surrealism itself did not survive, at least in the form that André Breton had envisioned, much beyond World War Two, as the main protagonists of the movement found it difficult to reconcile the fiery political rhetoric of their speeches and manifestos of the 1930’s with their headlong flight to the safety and security of New York once the anarchy they claimed to seek came goosestepping down the streets of Paris.

The Surrealists of Dalí’s early career, of course, were no strangers to using the press to further their own interests. Events were planned at which the major Surrealist figures of the day — usually writers and poets, as the movement’s dictatorial high priest, André Breton, did not fully accept the legitimacy of the visual arts — would offer performances of nonsense poetry or intentionally confusing presentations of political or social commentary. The Surrealist ideal was anarchic at heart, encouraging disruption and confusion rather than the creation of permanent works that risked becoming valuable commodities in the very economic milieu they hoped to overthrow. Dalí, however, proved to have an instinct that Breton could never hope to match: it was Dalí who attracted the well-heeled and the well-read to events and parties, not Breton, and for most people today Surrealism is epitomized by the Spaniard’s “paranoiac-critical” paintings, with their melting clocks and body parts, swarming with ants, arrayed like medical specimens in meticulously painted nightmare landscapes.

The fundamental ideas of Surrealism, while failing to survive in their own form, were absorbed into the artistic movements of the 1950’s and 1960’s, providing an intellectual basis for progressive and original art, music and literature for the rest of the century. Meanwhile, what we now know as surrealism (I think the capital “s” finally died altogether with Max Ernst and Pablo Picasso in the 1970’s) owes far more to the calculated goofiness of Dalí than to the rigorous intellectual and philosophical deconstructivism of Breton.

*

This week I placed an assortment of my artwork on public display at a local venue, the first time I’ve ever done such a thing. I, unlike Salvador Dalí, am piss-poor at marketing myself and my abilities: the very idea makes my head swim. At the same time, I find that my own incapacity in this regard gives me a better appreciation of the skills of a Lindsey Lohan, a Rob Zombie, or a Dalí, throwing themselves out in front of the public not necessarily with the hope that the masses will respond with love and admiration, but more in the manner of someone parking a gasoline tanker truck across the railroad tracks: everybody is going to have to stop and look, whether they like it or not.

Having come this far through this essay, you may by now be asking what the title has to do with anything. “The Metamorphosis of Narcissus” is, in fact, the name of a painting by Salvador Dalí — but more importantly, perhaps, it is also a reference to the myth of Narcissus, a young man so enamored of his own reflection in a pool that he is ultimately given immortality by the gods, transformed into the flower that now bears his name.

As the “Mad Spaniard” would attest, if you want the gods to smile on you, sometimes it’s up to you to get their attention first.

* * *

Leave a Reply