This weekend marks the traditional anniversary of the founding of Rome in 753 BC. Like so many historically important events, we know it happened, but the devil, it seems, is in the details.

There are two great legends of the founding of Rome, which are of equal cultural importance and popularity, but which are, unfortunately, mutually exclusive:

The first story involves Aeneas, the son of the goddess Venus and a mortal named Anchises. Aeneas is a prince of Troy who, in the aftermath of the Trojan War, is forced to flee his home, carrying his father on his back (Anchises has been crippled by a thunderbolt flung at him by Jupiter, the king of the gods, for bragging about his sexual exploits with the goddess) and leading his son Iulus by the hand. The refugees work their way around the Mediterranean, eventually ending up in Italy. Aeneas and his son manage to secure a place among the locals and establish the Roman nation (note the emphasis, here).

Cut to version two: This is the story of twin brothers Romulus and Remus, sons of the god Mars by a mortal woman, Rhea Silvia, one of the Vestal Virgins (remember that you can sometimes get pregnant without having to give up your virgin status as long as the father is a god: this is not the first time this explanation has been used.) Because of a prophecy involving the twins, Rhea Silvia’s uncle has the boys taken away to be killed — instead they are abandoned in the wilderness where they end up being nursed by a she-wolf until they are discovered by a shepherd who raises them as his own children. The brothers have a falling out, Remus is murdered, and Romulus comes down to us as the founder of the city of Rome.

To make the two stories mesh, Roman historians made Iulus, the son of Aeneas, the founder of a line of kings that leads down to the father of Rhea Silvia, and thence to Romulus. This allows us to have several generations of Roman kings long before the city of Rome ever comes into existence. A stretch, but one that the citizens of Rome have been happy to make for more than 2,500 years.

I have seen a vehicle carrying a bumper sticker with the motto “In God We Trust”, while a large Confederate battle flag is on display in the rear window. Presumably the owner of the truck did not know that these two cultural memes were designed, from their very beginning, to oppose each other, one representing the North; the other, the South.

On April 22, 1864, the United States Congress authorized the Mint to begin putting the phrase “In God We Trust” on coins. This was the culmination of a campaign by the Reverend M. R. Watkinson on behalf of a group of Protestant Christian leaders in the Union states to make some kind of statement that would demonstrate to all and sundry that God was clearly on the side of the North in the Civil War.

Here again, we see mutually exclusive stories being adopted as part of a single cultural canon: On the one hand, those who insist that Protestant religion was the guiding force behind the creation of this country use the existence of the national motto “In God We Trust” as evidence of the religious intent and convictions of the Founding Fathers; on the other hand, there is the purely historical fact that no official US motto referred to God in any way until after all of the Founding Fathers were long dead.

(In fact, “In God We Trust” did not appear on all US coins until after 1938, and was not mandated to appear on paper money until 1956, fully 180 years after the founding of the country. Not until 1966 did all currency in circulation bear that motto, only ten years short of the Bicentennial.)

*

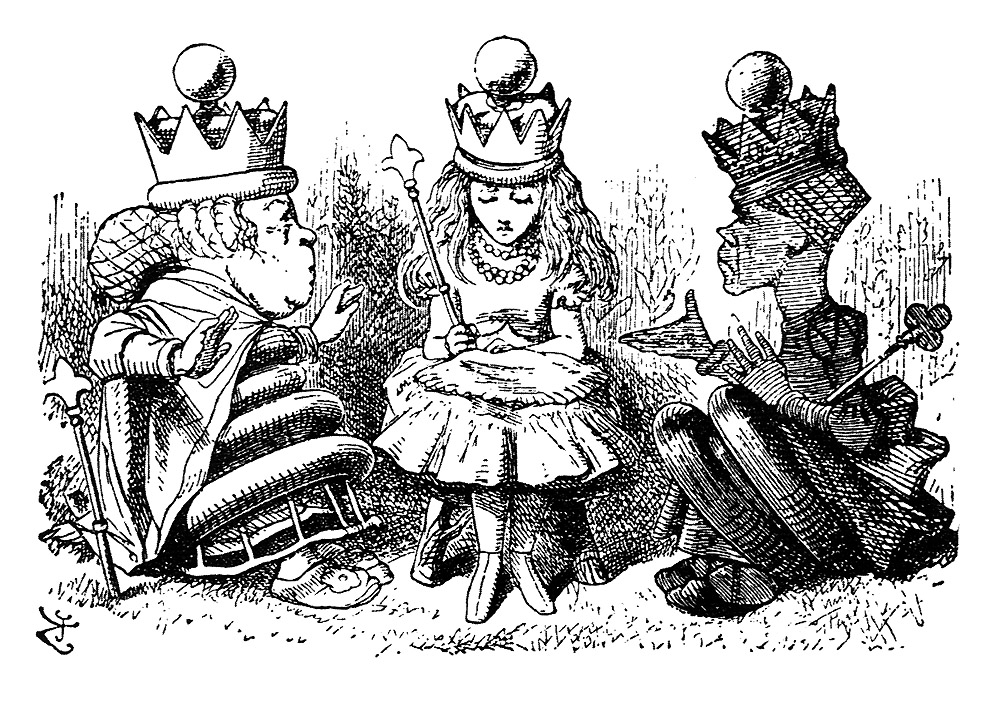

In Through the Looking Glass, by Lewis Carroll, the White Queen informs Alice: ‘Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.’

The White Queen is not alone in her willingness to stretch her credulity when it suits her. We all pick and choose the historical realities that we like, and then look for ways, however irrational, to tie the pieces together into a defensible whole.

- Later Egyptian pharoahs attempted to recreate the history of queen Hatshepsut, a highly successful female ruler, as a man, or as the wife of some other pharoah, because the concept of a female ruling an empire larger than their own was unacceptable.

- In Roman times, the Senate occasionally sentenced individuals or even entire families to what was known as damnatio memoriae, erasing every trace of them from the public record, as if they had never existed.

- There is a whole library of photographs of historical events during Josef Stalin’s regime in the Soviet Union that depict individuals who appear in one print, but then vanish in another — photos developed from the same negative, at different times. The regime manipulated the historical evidence to create a consistent narrative out of a capricious and wildly inconsistent series of political imperatives.

- After the death of Richard Nixon, there was a brief but intense period of historical “reinterpretation”, during which the saga of his rise and fall was recast to maximize many positive aspects of his time in office, even when the historical record did not support that narrative.

- Most Creationists believe that dinosaurs and men coexisted, or that dinosaurs never existed at all.

I turn fifty-four years old this weekend, and I’ve been taking some time to sort through a few old photographs from my childhood in the 1960’s in Montgomery and Boaz, Alabama. I still have memories that correspond to many of the people, places and events in these images, but very often I’m finding that what I see and what I remember don’t mesh very well. Events are out of sequence, or people are not as I remember them; even places seem wrong, distorted, foreign. What do I do? Discard my flawed memories? Disregard the evidence here in front of me? Accept six impossible things before breakfast?

Maybe none of the above. The Romans folded two stories taking place a thousand years apart into a single epic: all I have to do is pull together a few decades.

How hard can it be? History is, after all, only what we make it.

* * *

Leave a Reply