How much of the truth do we really want to see?

I just finished reading my first Joan Didion novel, A Book of Common Prayer (published in 1977, it has taken me a while to get around to it). This is another one of those cases where I can honestly say that it was a really good book, and I can also say, with equal honesty, that I’m glad it’s over.

To me, a story works or it doesn’t depending on whether I can find some connection to one or more of the characters in it. Really big explosions and a fast-moving plot are not enough: I want to be able to put myself into the action somewhere, believably. I enjoy trying to imagine how I would deal with what’s happening, if I were a part of those events. That’s not to say that I expect every story to include at least one mouthy and self-absorbed intellectual with — shall we say — a somewhat overdeveloped sense of self-preservation, but I expect any person of even minimal intelligence to know that sometimes it’s just not a good idea to go into the basement, or to go outside to investigate the strange noises in the woods, or to stay in Boca Grande when the phone lines go down and the US ambassador has just hopped the last plane for the border.

The Wikipedia entry on Joan Didion tells us that “…Her novels and essays explore the disintegration of American morals and cultural chaos, where the overriding theme is individual and social fragmentation.”1 Individual and social fragmentation was certainly evident in A Book of Common Prayer, and Didion covers some very difficult territory in this novel — the problem for me was that terrible things were happening to people in the book, and I found it so very hard to care. Again and again I found myself feeling sympathy for one character or another, and then that individual would behave in a way that I found so hard to comprehend that I just couldn’t maintain the connection.

When Little Red Riding Hood is accosted by the wolf, on her way to do a good deed for her elderly relative, we are concerned for her well-being. We approve of her mission, and we hope that she’ll come through without mishap. When Goldilocks, on the other hand, is discovered sleeping in Baby Bear’s bed, and is presumably dismembered as a consequence, we don’t criticize the bears. The little idiot wandered into their home, mucked around in their food, and passed out on their furniture.

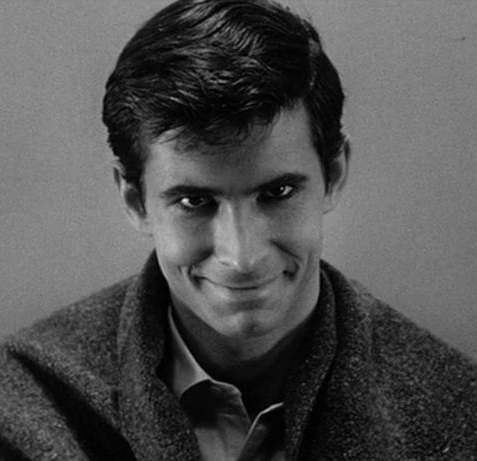

He’s not such a bad boy. He’s just misunderstood.

Fictional characters that are hard to love are not limited to a particular nationality or time frame — from Goldilocks in the fairy tale to Cathy and Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights to every teenager who ever got whacked at Camp Crystal Lake in the Friday the 13th movies, popular entertainment has provided us with a broad array of central figures that just don’t seem to be able to get with the program. Sometimes there’s a point to this depersonalization: the assassins in Mario Vargas Llosa’s novel The Feast of the Goat are not just a bunch of desperate men, but the embodiment of the victimization their country has endured at the hands of a brutal dictator. Their personal tragedies provide windows into the suffering of the nation as a whole; we are caught up in the greater injustice, even as we have a hard time becoming deeply engaged with them as individuals.

One of the things that makes Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho such a guilty pleasure is the way we relate to the character of Norman Bates. Sure, he’s a psychopath and all that, but we can sympathize with him, with his shyness, his awkwardness. The other characters are all users of one kind or another: a thief, a philanderer, a sleazy private investigator… We’re not altogether sure we want Norman (and/or his mother) to get caught, despite his insanity, despite his crimes, because we’re really not all that crazy about his victims.

Storytelling is a mirror that allows us to see ourselves as other see us. We become that character in a novel, or in movie, or in a song, and we play out scenarios that tell us things about ourselves that day-to-day life might never reveal. When I was growing up everyone had a comic book hero or a character from Star Trek with which he or she identified — these were not role models that we hoped to emulate, but rather they were versions of us that were functioning under circumstances completely different from our own. Watching them, we understood more about ourselves.

In Didion’s novel — and in novels that I’ve read recently by more modern writers such as Julian Barnes and Peter Carey — the mirror distorts and twists so that we’re forced to peer, squinting, into the mayhem to find even a glimpse of ourselves, fragmented and shadowy. It’s challenging, and not necessarily pleasant.

Will I read another novel by Joan Didion? Probably. There’s something to be learned even from a distorted mirror, and a story well-told is always worth the trouble.

But I can’t help but think that Goldilocks only got what was coming to her.

* * *

Leave a Reply