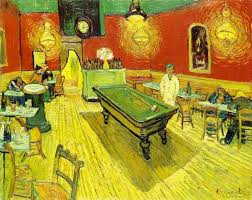

Some eateries need all the help they can get.Vincent van Gogh, “The Night Cafe”, 1888

At the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, our local temple of culture, an odious sculpture from the generally delightful Claes Oldenburg was replaced over the holidays by a delightful sculpture from the generally odious Jeff Koons.

Oldenburg, a icon of the sixties and seventies, has always been champion of a kind of oversized, over-the-top whimsy, taking such commonplace items as badminton birdies and clothespins and blowing them up to the size of Atlas rockets: the piece at Crystal Bridges, “Alphabet/Good Humor”, is a giant popsicle composed of letters of the alphabet melting together like fatty entrails, all painted a horribly suggestive band-aid beige.

Jeff Koons, a glib former Wall Street commodities broker, cheerfully admits that he takes no part in the actual production of any of the art that bears his name — even the concepts behind his works are appropriations of existing photographs, artworks, or consumer products. The Koons work that replaced Oldenburg’s popsicle is a giant beribboned heart, a somewhat trite Christmas tree ornament blown up to epic size, made of stainless steel and given an old-gold mirror finish.

Oldenburg’s piece was clearly not meant simply as decor. Especially in a restaurant setting, its gooey flesh-toned bulbousness is a bit disturbing; we’re supposed to respond to the idea as much as the image. Koons’ heart, on the other hand, is obviously nothing but decor. Like Mila Kunis or Channing Tatum, it’s there to be looked at: no great ideas, no deep meanings, nothing to challenge the spectator to question his or her own expectations and assumptions. Even the basic idea, that of the trivial household item grown gigantic, is simply Oldenburg’s signature concept picked up by Koons and given a high polish and an even higher price tag.

A famous bit of Picasso lore has it that he was once approached by a woman in a restaurant who asked him to create a picture for her. With his usual panache, the artist grabbed a pen and executed a quick sketch on a napkin, which he then offered to sell the woman for a considerable sum of money. Shocked, the woman exclaimed, “But it only took you five minutes to draw that!” “Madam,” Picasso replied, “it took me forty years.”

Art as restaurant decor is certainly no new idea: Paris is littered with minor masterpieces by French artists of the last two hundred years that were tendered in payment for food and liquor in places like Le Chat Noir or Café de la Rotonde; Mark Rothko’s suicide is thought to have been at least partly triggered by his horror at the thought of a crowd of “rich bastards” sitting around in the Four Seasons restaurant in Manhattan chowing down on caviare and filet mignon under several dozen square yards of signature Rothko canvas. I myself paid a few tabs during my salad days by sketching portraits of waitresses and bartenders in Birmingham, Alabama.

The line between Art and art, between high-concept high culture and something nice to hang over the sofa, is a fine one, more of a suggestion than a barricade. Much of the work hanging in places like the Louvre, the Tate, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art spent at least part of its history as a component of someone’s interior design scheme. After all, most of the people who buy art are not decking the halls of a museum: they’re buying something they like to look at, or that they think will be worth more some day than they’ve just paid for it, or — let’s face it — they needed to fill up a space over the sofa. Will the art of today be the Art of tomorrow? Who knows?

In art, as in politics, there are two final arbiters: money and history. Jeff Koons’ work brings in big bucks; whether it has any real significance as Art remains to be seen. Oldenburg’s floppy food and giant household items have been around for several decades now, and although they’ve lost some of their glamor as the goofiness of Pop Art has faded into the drug-addled mists of the nineteen-sixties, they still have a place in the art books, museums, and public parks of America. Arguably, Koons’ monumental balloon dogs and kitschy polyester statuary tableaux would not exist had Oldenburg not paved the way; at the same time, Oldenburg may retain some of his old-master status because of his role as precursor to more recent big-dollar snake-oil impresarios like Koons.

What will replace Koons’ “Hanging Heart” when the museum restaurant crowd gets bored with it? Since Damien Hirst is not American but British, we can assume that we won’t be treated to a pickled shark in a tank of formaldehyde or half a sheep under glass, but if history is any guide, the options are still limitless.

And that’s how it should be.

* * *

Leave a Reply