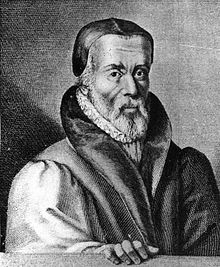

William Tyndale, c. 1490 – 1536.

Anyone who knows me may be surprised to learn that I own three Bibles (the Revised Standard, the New English, and the King James), as well as the Book of Mormon, the Nag Hammadi Scriptures, the Apocrypha, and an English translation of the Qur’an. I know the difference between an Apostle and an Epistle, I can list the twelve sons of Jacob*, and I can whip out a quote from the four Gospels for just about any occasion.

None of which, in my case, has anything to do with religion. I am not religious: I am, however, a student of history, and as such I can hardly ignore the profound impact that organized religion has had on human culture over the last few thousand years.

I mentioned that I own three different English translations of the Bible: In fact, there exist approximately 450 English-language Bibles, ranging from partial transcriptions into Old English appearing only a couple of centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire all the way to Eugene Peterson’s The Message, completed in 2002.

Why so many?

As with any document so deeply embedded in a culture, control of one can imply control of the other: shades of meaning can support one political faction, one viewpoint, one set of social mores, over the competitors. Influence over the words translates to influence over the people. In modern times we have but to look at the vast differences between various interpretations of the second amendment to the US Constitution to see how divisive these nuances can be – an entire branch of our government exists for the sole purpose of resolving ambiguities in our written body of law.

On October 4, 1535 – 479 years ago today – William Tyndale and Myles Coverdale printed the first complete Bible in English translation. The book was published somewhere on the European continent, financed by various members of a wealthy Dutch family.

When that first edition of what came to be known as the Coverdale Bible was printed, Henry VIII was king of England, and was in the process of rearranging his own relationship to organized Christianity. The question of what language the Bible should appear in was not uppermost in Henry’s mind; an acceptable English translation was something he was prepared to deal with later. Much later.

For the Mother Church, on the other hand, these were difficult and complicated times, and any drift from official dogma was the thin end of the wedge.

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 turned out to be a very good thing for much of the rest of Europe, as highly sophisticated Byzantine Greeks fled the Turks and scattered into the West. This shot in the arm stimulated thinkers like William Tyndale into examining their own cultures more objectively, and many realized that the medieval worldview had created a cultural desert in places like England and France, stifling ideas and retarding development. Tyndale — among others — began to absorb classical thought and intellectual tools and to use the lessons they learned to reorganize the clumsy and limited Middle English of their day into a newer and more responsive tongue. The fertile language of Shakespeare and Marlowe and the other writers and thinkers of England’s Renaissance was a direct result of this much-needed overhaul.

In fourteenth century England, John Wycliffe had translated chunks of scripture into Middle English, triggering a backlash by the Church against any rendition of the Biblical texts into a language other than Latin. Greek and Hebrew texts existed, of course, as sources of the Latin canon, but English and German were the languages of peasants and shopkeepers rather than scholars and priests, and were not considered acceptable vehicles for Scripture.

In 1517 Martin Luther began stirring the pot more vigorously, and the rift between Lutherans and Catholics was cemented in 1521 with the Edict of Worms. Luther’s translation of the Bible from Latin into everyday German had effectively cut out the middleman in the search for salvation. Now anyone who could read could get his religion directly from the source: the vast and expensive machinery of the Church at Rome was no longer a necessary intermediary.

By the time Tyndale and Coverdale produced their translation, Pope Paul III was not in a mood for polite discussion. To add insult to injury, Tyndale was not merely a translator: he was a scholar who had relied not only on the official Latin Bible for his source material, but also older Hebrew and Greek texts, correcting what he saw as mistakes that had crept into the Latin works.

Tyndale survived the publication of his Bible by only a year: with the ink still wet, he was arrested, tried and condemned for his efforts, and in 1536 he was strangled, then his body burned at the stake. His dying wish was that King Henry would adopt his translation for the English church and two years later Henry commissioned what would come to be known as the Great Bible, based on Tyndale’s work. In 1604 James Stuart, King of Scotland and England, the grandson of King Henry’s older sister, would commission yet another English Bible, a tweak of the Great Bible designed to appease the Puritans, a faction within the English church who had objected to what they perceived as errors in the previous versions; this is the book we now know as the King James Bible.

Since the days of James I, an enormous array of scholars, dogmatists, swindlers, mystics and true believers have revisited the job. Some translators have returned to the earliest verifiable sources to recreate something they hoped would more closely resemble the scriptures of the Church’s first centuries. Others have rewritten the King James version into a modern idiom, appealing to a less-erudite audience bewildered by the intricacies of Jacobean English. Still others have applied the filters of their own cultural outlook – discarding or obscuring some passages, amplifying others – in order to confirm the supremacy of a specific view of society.

In the end, of course, we’re all still a very long way from home. Even by Tyndale’s day, patriarchs and popes, kings and committees had all reworked and rearranged the available material to fit what they believed it was meant to say. Over time the preconceptions and assumptions of every age were imposed on the text, leaving us with a palimpsest of history, something that would be unrecognizable by the authors of the earliest contributions.

In the end, this confusion is part and parcel of both history and faith. For the scholar, the Bible is a core sample reaching down through layers of time, taking away random bits of each era and bringing them up where we can examine them with our modern eyes; for the believer, the whole process, with all its twists and turns, is part of a divine plan, resulting in a finished product that could not have come into existence any other way.

My grandfather, a Baptist minister of the old hellfire and brimstone school, saw the Bible as the divine word, replete and eternal, but he was not afraid to ask questions, to dig into the maps and the scholarly concordances in search of context and perspective.

I, on the other hand, even without the added dimension of religious faith, can still appreciate the passion and devotion of the work, and from my own perspective, I don’t think it has to be the Good Book to still be a good book.

*Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, Asher, Issachar, Zebulun, Joseph and Benjamin

* * *

Leave a Reply