“The Tower of Babel” by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1563) — We used to think it was a good idea to understand each other.

I often read novels by Latin-American authors in the original Spanish.

I know, I know: at least part of the reason for doing it is just to be able to make statements like that — we all carve out these nuggets of self-esteem where we can find them — but the fact remains that some stars really do shine brighter in the universes that gave them birth.

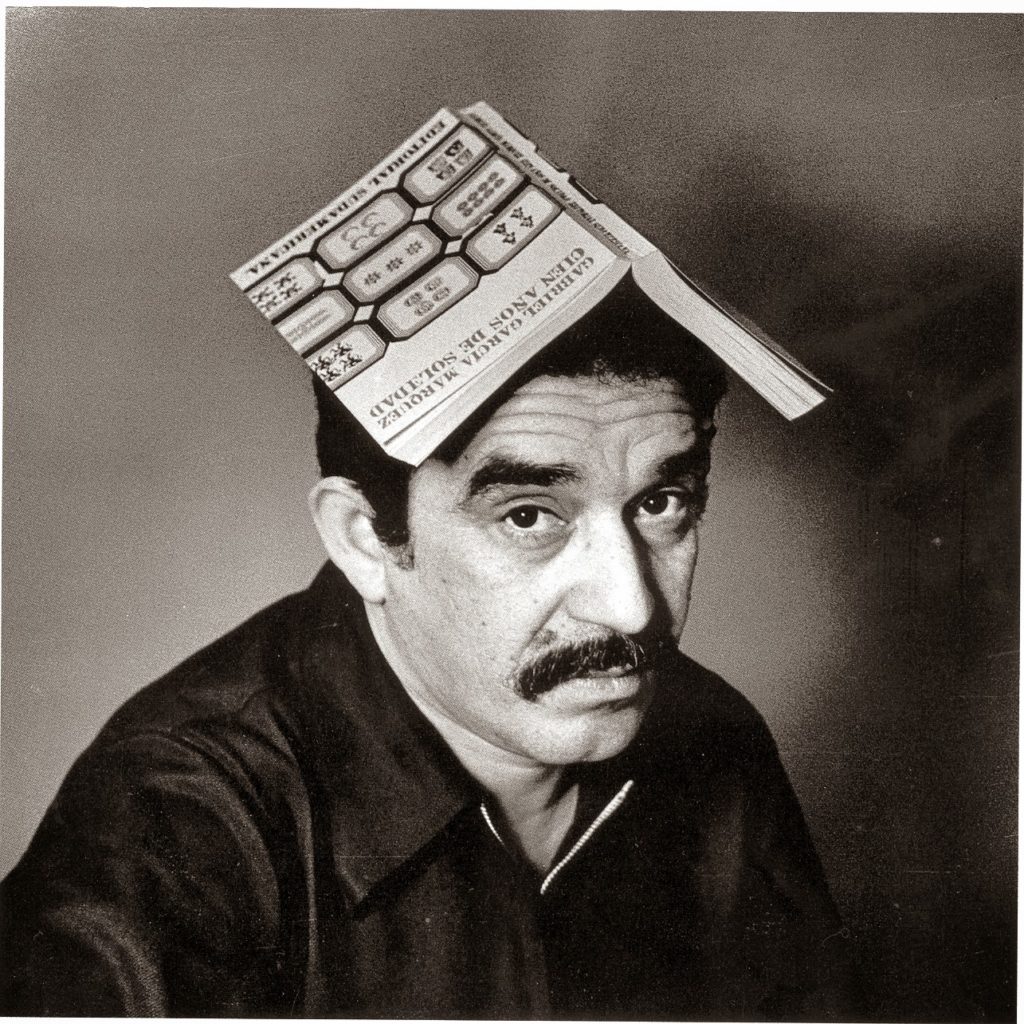

Argentine authors Julio Cortázar and Jorge Luís Borges can be read in virtually any language; their themes, their characters and situations, are universal. Others, however, such as Colombian Gabriel García Márquez and the recently deceased Mexican author Carlos Fuentes (in his historical fiction) present stories of people and places and events that could only exist in the unique historical and cultural environments in which they are set. We read Márquez’ One Hundred Years of Solitude or Fuentes’ Terra Nostra as spectators, outsiders vouchsafed a glimpse into a world that is not ours, that can never be ours. In cases like these, a knowledge of the language helps, but in the end it is only a code that’s been broken: the underlying message remains obscure and ambiguous.

At the moment I’m reading a novel by Philip Roth, which takes me about as far from Octavio Paz or Mario Vargas Llosa as you can get. Roth is a quintessentially American writer — by which I mean North American — documenting a big chunk of the American experience, that of the children and grandchildren of Jewish immigrants during the middle decades of the twentieth century. His language is English, and it’s an English that is simple, clean and transparent, eminently accessible; yet still, I find myself peering in through the windows at his scenes of family life in Chicago or New York or Boston, excluded, a little mystified.

Gabriel Gárcia Márquez, 1927-2014

My ancestors came to this continent centuries ago, and dissolved into the soil like a bucket of muddy water dumped on a plowed field. They weren’t called “immigrants” then, they were “pioneers”, but they were still refugees — no less than the post-Holocaust characters in a Roth novel — fleeing the grinding weight of European history that had destroyed their parents and would have destroyed them had they stayed put. I, on the other hand, am a military brat/farm boy/college dropout, born and raised in Alabama. The experiences of educated men whose parents speak a different language in their bedroom at night than they do at the dinner table, whose religion is both a burden and a shield, whose history is so much bigger than they are: all this is no less foreign to me than the ghost of José Arcadio Buendía pestering Ursula the maid in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Canadian Margaret Atwood writes novels whose characters are instantly recognizable, they are the sisters, mothers, friends of male readers like me, people I know. And yet, and yet — once more, they are still other than me: I feel a vast sympathy for the bullied and lonely little girl in Cat’s Eye, but I’m her brother/father/neighbor, not her. I can’t know — not really — what it’s like to be a thirteen-year-old girl, no matter how deeply Atwood makes me care about the child.

In the end, this barrier always exists at some level: a boundary of gender, of culture, or history beyond which we can never pass. We all exist in universes that are similar, congruent, but only parallel: they never intersect. To communicate, we have to make the effort to empathize, to acknowledge the value of something that we can never really understand, and this is difficult.

“Then began I to dream a marvellous dream,

from the Prologue to The Vision Concerning Piers Plowman, by William Langland, circa 1370

That I was in a wilderness wist I not where.

As I looked to the east right into the sun,

I saw a tower on a toft worthily built;

A deep dale beneath a dungeon therein,

With deep ditches and dark and dreadful of sight

A fair field full of folk found I in between,

Of all manner of men the rich and the poor,

Working and wandering as the world asketh.”

I live in Arkansas, where most of the political rhetoric would make Kim Jong-eun cringe. This is the state with, statistically, the least-educated political class in the country, representing the second-least-educated electorate. I read the quotes in the press, I look at the campaign flyers that appear in my mailbox, and I feel a sense of unease mixed with disappointment, struggling to accept the idea that not only is this who we are, but that this is all we want to be. It’s far too easy, at times like this, to look down at the people and the process from atop my great tower of words and ideas and believe myself somehow better than all that.

But in the final analysis, I’m not better, I’m just different, and if I can’t make the effort to reach across the gap, at least in my own comprehension, then I’m not even different. I can’t justify the belief that I occupy some sort of intellectual high ground if I can’t use that vantage to see further, and to try to understand — to empathize with — what’s going on in the great “fair field full of folk” before me.

I have to keep reminding myself that no matter how strange things are in that other universe, there’s always a story in there somewhere, just waiting to be read; but I admit that sometimes I’m frankly afraid, when I hear the soundbites and read the speeches — I wonder if there’s going to be time for anyone to learn the language.

* * *

Leave a Reply