Holmes never actually said “Elementary, my dear Watson,” but Basil Rathbone made us wish he had.

One-hundred seventy-one years ago, Edgar Allen Poe published his “Murders in the Rue Morgue”. A genre was born, and I, for one, am thankful. I do love a good detective story, now and then.

Poe’s investigator was an individual named Dupin, a “gentleman” in the most traditional sense of the word, a man of independent means who did not have to work for a living, but who could amuse himself however he chose: in this case, by investigating a sensational murder that he and his companion had been following in the press.

Edgar Allan Poe was paid $56 dollars for “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”, a princely sum by the standards of the time. Writers were often paid in copies of the final product, rather than cash, and what cash payouts there were were generally small. Not until the modern era of the “superstar” novelists, writers such as Stephen King and J.K. Rowling, has fiction writing been a reliable source of income for many of its practitioners.

The gentleman of leisure, of course, was a staple of literature in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as these were men who could afford to devote their time entirely to the pursuits that furthered the aims of the author, rather than having to disappear from the plot for a large part of every day to report to a job somewhere. Not until the 1880’s did Arthur Conan Doyle open up some space for the working man with “the world’s first consulting detective”, Sherlock Holmes, who was actually paid for his services — but even Holmes had the luxury of accepting only the cases that interested him.

The twentieth century saw the professional police detective come into his own. Previously only a sort of foil, a buffoon like Conan Doyle’s Inspector Lestrade, whose ignorance and working-class manners provided a backdrop to the superior intelligence and breeding of the hero, the policeman gradually worked his way up in the world: during the course of the Lord Peter Wimsey novels of Dorothy L. Sayers, Charles Parker, an ordinary Scotland Yard detective, becomes not only a close friend of the aristocratic sleuth, but eventually marries his sister.

Police detectives worked “real” jobs, for a regular paycheck, a concept that resonated with a working-class audience. The “police procedural” was introduced in the US and England in the 1930’s, and quickly became a staple of detective fiction. These stories focused on the job itself, rather than on a specific crime; in some cases there might be more than one investigation underway during the course of the book, with the only common element being the detectives themselves. The crimes were solved by ordinary people, just doing their jobs, and readers recovering from the Great Depression and coping with the Second World War could feel a connection.

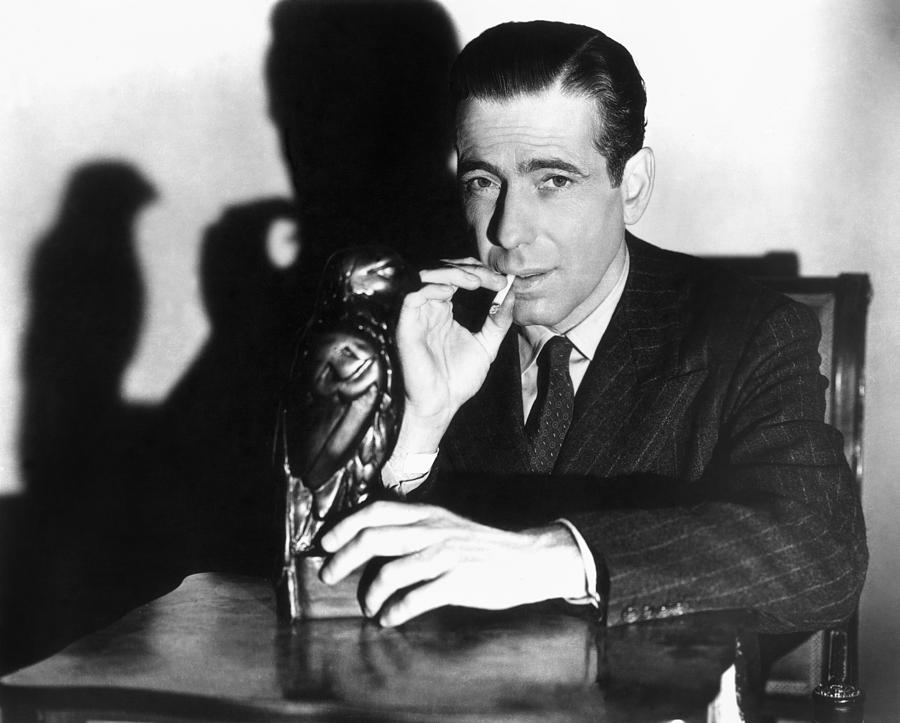

A close relative of the police detective — although often the black sheep of the family — was the private investigator, usually a former policeman, sometimes occupying a moral position of some ambiguity with regard to his former profession. In the 1930’s the “PI” evolved into a form of anti-hero: Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe were men who operated at a moral level barely superior to that of their villains; Nero Wolfe was grotesque and mercenary; Perry Mason’s first loyalty was to the client who was paying his fee. By the 1950’s, characters such as Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer were even more unsavory than the criminals they pursued.

The game of “Clue” was originally invented in Britain in 1944, under the name of “Murder!”, intended to serve as a way for people stuck in bomb shelters to amuse themselves. When the game was released commercially in 1949, the name was changed to “Cluedo” in England (“clue” plus “ludo”, Latin for “I play”), and to “Clue” in the United States (where Latin has never been as much a part of the curriculum.) The current version of the game features six suspects, six weapons, and nine rooms, for a possible 324 different possible murders.

Apart from the wide variety of detectives, the involvement of the reader also varies a great deal throughout the genre. A few authors give us first-person narratives — often from the point of view of the detective, more rarely in the voice of the criminal, as in Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. By contrast, in Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, we see everything in a completely external view, with no sense whatever of the inner thoughts and motivations of the characters, apart from what may be suggested by their actions. The Ellery Queen novels — written by two men working under one pseudonym — invite the reader to attempt to solve the crime once he or she has reached a point in the book at which sufficient information has been provided to do so; the reader becomes the detective.

When Poe wrote his Dupin stories his focus was not so much on the crime or the criminal, but on the mechanism of solving the crime; murder was an excuse for a bit of mental exercise. A critic once observed that in Agatha Christie’s novels murder had been reduced to a breach of decorum. The argument has certainly been made over the years that the objectification of violence and death that characterizes much detective fiction is unhealthy: while Dupin is simply solving an interesting puzzle, the fact remains that two women are very gruesomely dead.

But there, perhaps, lies much of the appeal. We, the readers, are very much alive in the midst of the murder and mayhem, and can enjoy the sense of godlike security that a novel provides. Is this a good thing? A bad thing? In the end, it probably doesn’t matter: we humans are never going to completely outgrow our tendency to bonk each other on the head from time to time, and as long as that’s going on, it’s going to be someone’s job to deal with the consequences.

The rest of us can try to match wits with killer and hero from the comfort of our La-Ze-Boys, and if the going gets rough, we can always skip ahead a few chapters to see what the butler’s been up to.

* * *

Leave a Reply