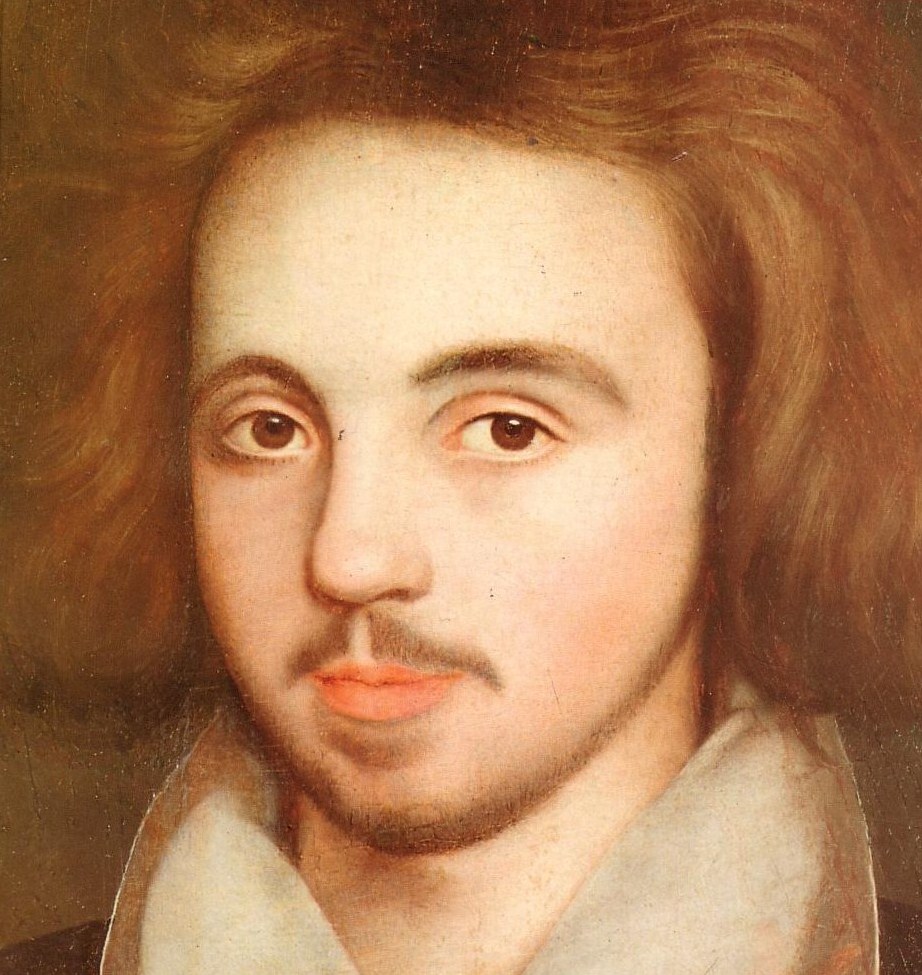

Kit Marlowe, a contemporary of Shakespeare: He also wrote some great plays, but highbrow? Not by a looong shot.

A friend recently pointed out a DVD of a new performance of William Shakespeare’s “King Lear” and observed that she generally did not enjoy such “highbrow” entertainment, even though the star of that particular staging was an actor she adored. If Shakespeare could hear such sentiments, I think he would be both flattered and very, very surprised.

There are no hard and fast rules about what is “highbrow” and what isn’t: like pornography, we all generally know it when we see it. Shakespeare, opera, live theater generally, and movies with subtitles are highbrow; professional wrestling, monster truck rallies, the NFL, and fireworks are not. At different times, however, the guidelines have been very different.

In Shakespeare’s day, there was standing room available in front of the stage for the “tanners, butchers, iron-workers, millers, seamen from the ships docked in the Thames, glovers, servants, shopkeepers, wig-makers, bakers, and countless other tradesmen and their families”1, while the wealthier patrons took advantage of balcony seating, the best of which even included cushions. Audiences were rowdy, pushing and shoving, eating and drinking, sometimes shouting at the actors, all rather like a midnight showing of “The Rocky Horror Picture Show.” Theater was a popular entertainment, not just in the sense of being enjoyed by a large audience, but also “popular” meaning “of the people”. A sailor and his girlfriend attending a performance of “Julius Caesar” need not know anything about the history of Imperial Rome: they were there for the comic bits and the fight scenes. A good play, like a Bugs Bunny cartoon from the fifties, had something for everybody, regardless of age, education or social standing.

Modern theatergoers sometimes puzzle over the archaic English of Shakespeare’s plays, but for the audiences of his day, there were even bigger problems: the Bard was prone to making up words when nothing suitable came to mind. Words he invented include: disgraceful, coldhearted, fretful, useless, zany, successful, scuffle, retirement, hostile, and monumental, all words without which many of my job evaluations over the years would not have been possible.

Until well into the twentieth century, opera likewise was simply a form of entertainment. In the days of Puccini or Verdi, every brickmason and baker’s assistant could sing the great arias: opera was a common language, grand stories of love and hate and jealousy and violence, with singable music and stars whose private lives were as much a part of the experience as the costumes they wore on stage. Today we tend to think of opera as something always being presented in a foreign language, but that’s a lot like saying that television programs are only produced in Portuguese just because, in Brazil, they usually are: like any other popular entertainment, operas were written in the language of the audience — Italian in Italy, certainly, but also French, German, Russian and even, yes, English, in the countries where those languages were spoken. Themes were familiar ones, from history (Verdi’s “Aida”), politics (John Adams’ “Nixon in China”), mythology (Wagner’s “Ring” cycle) to romance (Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess”) and social commentary (Benjamin Britten’s “Peter Grimes”). Like the plays of Shakespeare and Webster and Christopher Marlowe, this was an art form intended to reach as wide an audience as possible, not just an educated elite.

What’s happened to close off this vast area of human enterprise from the majority? Dress codes haven’t helped: a laborer in Shakespeare’s day showed up at the theater in the clothes he wore every day; today, we often feel that we’re expected to dress up to go see “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” or hear “Turandot”. Ticket prices also are a strain on many budgets: many concert halls are expensive and ornate monuments to money rather than simply places where people can gather to be entertained.

But that being the case, why don’t we just stay home and watch these things on television? We can wear our pajamas if we like, and eat popcorn — no one will care.

Personally I believe that a great deal of art — by which I mean great books and movies as well as opera, plays, and music generally, as well as visual art — has been subjected to what I call “the Tuxedo Effect”: People wear tuxedos not because they are sensible, or comfortable, or even attractive on a lot of people, but because they can afford to: the tuxedo separates the guy with the Mercedes from the guy parking it for him. We like to be able to distinguish ourselves from the people below us on the social ladder, and creating a costume or a custom that excludes “the others” makes it easier for us to define and reinforce our status. The process works the other way, too: we look at those people “above” us in society’s reckoning — the ones with bigger houses, more money, nicer cars, more expensive educations — and we look for ways to laugh at them, to be able to look at the differences and say: “So what? I don’t care about that, anyway.”

By the same token, of course, the self-styled intellectual often cuts himself off from a great deal of human expression simply because he feels that it is somehow beneath his dignity: this is the person who refused to watch the plays of Kit Marlowe in his day or to listen to the music of Bessie Smith in hers, because they just weren’t sufficiently “highbrow”. When George Gershwin’s opera “Porgy and Bess” first premiered, many critics considered its themes and characters too working-class for “real” opera.

In the end, unfortunately, we all lose: the arts become an “elite” entertainment, and we elevate the work of the playwright or composer to some sort of intellectual pedestal, accessible only to the cognoscenti, the educated few. The soldiers and gravediggers, the cleaning ladies and the farmers and the grocers, the people just like the people who populate those plays, are excluded — and, more sadly, exclude themselves — from an art form that was invented for them, and about them, and often by individuals very much like them.

So, why not give it a try? Let your guard down for a moment and listen to a little bit of something different, something you’re not used to hearing, something that maybe you always thought was over your head: it’s not, you know. Watch a recording of “As You Lke It” or “The Duchess of Malfi” or “Sweet Bird of Youth”. Maybe even go down to your local community theater or college drama class and see the real thing.

If you ever thrilled to Elmer Fudd singing “Kill the Wabbit” in the classic Bugs Bunny cartoon “What’s Opera Doc?”, then Wagner’s “The Valkyrie” is waiting for you out there somewhere. If you paid a buck back in the day to go to the movies and see Anne Francis frolicking with Robby the Robot and an only slightly less mechanical Leslie Nielsen in “Forbidden Planet”, look up Shakespeare’s “The Tempest”.

You might just be surprised at how high your brow can go.

* * *

Leave a Reply