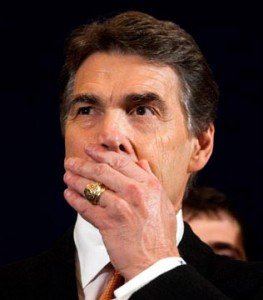

“Oops.”

Back in the mists of history — about the fifth grade, I think it was — a teacher informed me that my mouth seemed to operate a bit too much ahead of my brain. Since fifth-grade teachers are prone to such Delphic utterances, I just nodded and said “Yes, ma’am,” as I always did, and continued on my way, without the slightest idea what she was going on about.

Time has not improved my mouth-brain coordination, but over the intervening decades I’ve begun to understand what she meant.

It’s not just me, of course. Every public figure is familiar with the head-smack moment, when he — it’s usually a he, except for Sarah Palin or Michele Bachmann — realizes that the microphone is still on, and that there is absolutely zero possibility that the stupid thing he just said will not be appearing on the front page by morning. We’ve all made that all-too-personal comment in Facebook, connecting only seconds later with the fact that not only our own mothers but several million other mothers are reading it, clutching at their chests and gasping. Marriages have crashed and burned on the basis of a dozen words in the wrong place, at the wrong time.

“I could have gone right through the floor.”

“I don’t know what I could have been thinking.”

“The words just popped right out of my mouth.”

Some people, of course, say stupid things intentionally: shock jocks, radio talk show hosts, Al Sharpton — these are individuals who make their living through outrage, whether their own or someone else’s, and we encourage them to rush up as close to the precipice as possible every day, watching breathlessly for that Sandra Fluke/Tawana Brawley/Rutger’s Women’s Basketball Team moment when we can sit back and congratulate ourselves that we knew it was going to happen, sooner or later.

Gross lapses in verbal judgement are often referred to as “gaffes”. This is an word that has only been used in this context since about 1900; it shares its origin with the word “gaff”, meaning a hook on a long handle used to snag fish and drag them into the boat. “Gaff”, in turn, comes from the Western Gothic “gafa”, meaning “hook”. The word was probably jumbled together in the nineteenth century with a similar term in an obscure Scottish dialect that means “loud talk”, giving us the present interpretation.

But for the rest of us, conversation is a crowded playing field that we have to get across, time after time, inflicting as little damage as possible en route, either to ourselves or to our friends and neighbors, and the game plan usually falls apart as soon as the ball is in play. My father, for most of his life, got around the problem by simply smiling enigmatically and saying absolutely nothing. This seemed to work for him, but I am made of different metal: I rush in where angels fear to tread, trusting to fancy footwork and speed to get me through, never passing up an opportunity to jump in with a witty aside, a mixed metaphor, or a useful tidbit of information. Somebody has to carry the ball, after all.

We are surrounded today by words. According to the latest UNESCO data available, over a million books are being published each year, worldwide. As of early 2011 there were 156 million public blogs in existence (not including this one.) Halfway through last year the number of tweets going out per day passed 200 million. Facebook has about 840 million active users. We pick and choose; read this, discard that, and dialogue is usually limited to hitting the “comment” button and saying something cute.

Talking to people face to face, though, is a different ball game, more nuanced, more demanding. The risks to self-esteem are greater. The hazard of saying something really, really stupid right to someone’s face is harder to avoid. Ask Mitt Romney, or George W. Bush, or Rick Perry how scary it is when your mouth is moving and everybody is staring at you, recorders at the ready, just waiting for the wrong thing to come out.

• Edgar Allen Poe called the problem “the imp of the perverse”.

• Sigmund Freud — well, we won’t go there.

• In legal terms an inappropriate comment made without any intent to do harm is called an “excited utterance.”

• A “Kinsley gaffe” is defined by the New York Times as a remark made by a public figure who blurts out the truth by accident.

We’re not all as graceful as that quarterback in high school who seemed to dance along the field without ever touching the ground hard enough to bruise the grass. Some of us end up chewing the grass more than we float over it, but maybe that’s what the game is all about: everybody plays, and we work together to get around our limitations. I’ve learned to apologize when it’s needed, and take my lumps when an apology isn’t enough. I’m a talker, and nothing will ever change that. I believe in conversation, even if sometimes I play it like a contact sport, and I think any society benefits from people talking to each other, face to face, whenever the opportunity arises. I know that’s been said so often that it sounds like a Hallmark card, but it’s true: the strange or foolish pronouncements that end up all over the morning news might make sense if somebody thought to ask what was actually meant, or if the speaker took the time to explain himself, honestly and in good faith. We’re sometimes a little too quick, I think, to jump on that one damning sentence or misguided attempt at humor, without really engaging with what’s been said, and under what circumstances.

Sometimes an atrocious remark is just that — atrocious, unforgivable, a sign of a deeper personal disease. Other times, though, we just say stupid things because we’re excited or distracted, and we’d be more than happy to take the foot out of our mouths and try to explain or apologize, given half a chance.

Then, maybe, we could all have a good laugh and move on to the important things, before events overtake us and there’s nothing left to do but try to repair the damage, hoping that it’s not too little, too late.

* * *

Leave a Reply