Juana Inés de la Cruz, at about age 15.

On the Mexican 200-peso note, in place of the usual frock-coated revolutionary leaders and be-feathered Aztec potentates, is a portrait of a woman, wearing the cowl of a nun.

She’s an attractive woman, but with a gaze that’s steady, even stern: she doesn’t look patient, or particularly warm, but her face is decorating a piece of currency, so you have to think she might be someone worth knowing.

That woman is Sor Juana, Juana Inés de la Cruz, a Hieronymite nun, and one of the greatest minds of the 17th century.

Juana Inés de la Cruz was a prodigy, a child genius who could read and write by age three, and by the age of thirteen was teaching Latin to other children and composing poetry in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. Despite rules prohibiting young girls from reading books other than religious pamphlets produced specifically for the purpose, by fifteen she had become famous for her ability to answer questions and carry on discussions on a wide range of topics without hesitation or uncertainty.

Juana is said to have been a voracious reader, but entirely on the sly, borrowing books from her grandfather’s library and reading them in secret. Women at that time were considered biologically incapable of grasping abstract concepts, and what education was available to young girls was limited to devotional reading, the French language, and treatises on housekeeping, clothing, and comportment. Barbie had not been invented yet, but I suppose the underlying assumption was similar.

At the age of sixteen, Juana proposed to disguise herself as a man in order to enter the university in Mexico City. This scheme was thwarted by her mother: nice girls did not pass themselves off as men and spend time in male-only institutions. For a young woman of her beauty and accomplishments, the only socially acceptable options available to Juana were marriage and motherhood, or the Church, and by the age of sixteen, Juana had become much sought-after as a potential bride.

At the age of seventeen Juana Inés de la Cruz became a nun.

The poetry of the nun known as Sor Juana is passionate stuff — not at all what one expects from a woman at her station in life. She uses the language of love, of disdain, of passion wasted, of devotion both returned and unrequited, to engage in a dialogue with her reader about the nature of human desires, and the tools available to pursue those desires. Nobel Prize-winning Mexican poet Octavio Paz has speculated that much of Sor Juana’s writing is a sort of code, presenting different layers of meaning, from the surface discussion of human needs and romantic and spiritual love to deeper investigations into the place of the human mind in a vast and unknowable universe.

It is difficult, at first, to understand why a woman whose mind ranged so far and so wide would be willing to place herself under the constraints of a monastic religious order. We forget, however, how limited her choices were: women of the Catholic New World existed as accessories to men, first their fathers, then their husbands. As a nun, replacing the father and husband with Church hierarchy, Juana could avoid the entanglements of marriage, with the social and personal restrictions and requirements that would entail; and as a nun there were avenues available to her by which to interact with the world of ideas.

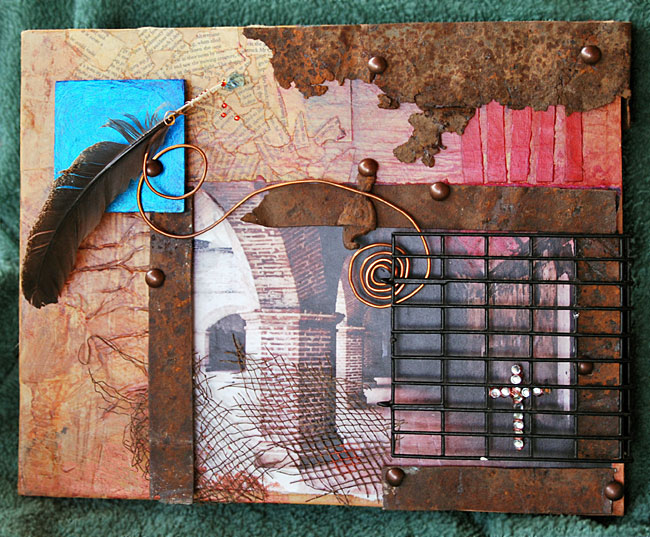

“Sor Juana”, mixed media assemblage by Dave Holcomb.

There were drawbacks to this compromise: by the time she had reached her early forties, her writings, especially her arguments for allowing advanced education for women, had attracted unwelcome attention from the Church, and at the age of 42 she sold off her enormous library to avoid further scrutiny and possible punishment.

At the age of 43, after nursing fellow nuns through an outbreak of the plague, Sor Juana herself fell ill. She died on the 17th of April, 1695.

Earlier today I put together a small artwork dedicated to Sor Juana: I had originally conceived of the theme as being that of an escape from the convent; on reflection, I began to think more in terms of an escape to the convent.

In the end, of course, a mind like that of Juana Inés de la Cruz doesn’t need to escape: there simply aren’t walls tall enough to hold it.

“Enough, my love, of cruelty, enough;

let brutal jealousy no more torment you,

nor let low fears your mind’s peace countermand

with foolish fantasies, with empty signs,

for in a liquid form you’ve seen and touched

my heart unloosed, dissolved between your hands.”

— from “In which she satisfies suspicion with the rhetoric of weeping” by Juana Inés de la Cruz; translation by Alix Ingber, 1995

* * *

Leave a Reply