A few days in Fort Lauderdale would have made all the difference.

There’s something jarring about looking around on a beautiful Spring day and seeing teenagers roaming the sunlit streets in Goth gear. Even after all this time, the black clothes, eyeliner, and prison-white skin all seem better suited to overcast skies and dim, windowless indoor spaces than balmy breezes and tulips. I have no particular issue with the look — I was in high school in the 1970’s, so I have much to answer for myself, as far as teen fashion goes — but I wonder if many of these kids realize where the whole thing started.

In history, the Goths were a vigorous (and prolific) people of Scandinavian or Germanic origin who migrated south and west from the Baltic Sea region over a period of centuries, eventually overrunning vast swathes of Europe, through France and Spain as far as North Africa, eastward into Russia and southward across what is now Italy.

Physically, the Goths were fair-skinned, often blond and blue-eyed; their descendants can still be seen in the northern parts of Spain and Italy where the Goths were the dominant people from the fall of the western Roman empire until well into the Middle Ages. They were physically robust, culturally straightforward: much of the history of the Goths centered around nothing more complicated than a long search for a permanent, secure homeland. The Gothic invasions of the Roman Empire, and their role in the eventual collapse of the empire in Italy, was due not so much to any desire to rule as simply a sense that they would never find security without power. They sought not to destroy the empire, but to wrap themselves in it.

During the Middle Ages there arose a distinctive style of church architecture, characterized by great vertical sweeps and obsessive delicacy of design, which later scholars described as “Gothic” (by which they meant “Germanic” or crude, as opposed to the “Romanesque” style emanating from Italy and owing much of its character to Roman leftovers). Gothic churches appeared in northern Europe and Spain, but rarely in Italy or Greece, whose art and architecture were considered the model by which all other styles were judged, so the cognoscenti of the Renaissance tended to view the Gothic model as barbaric.

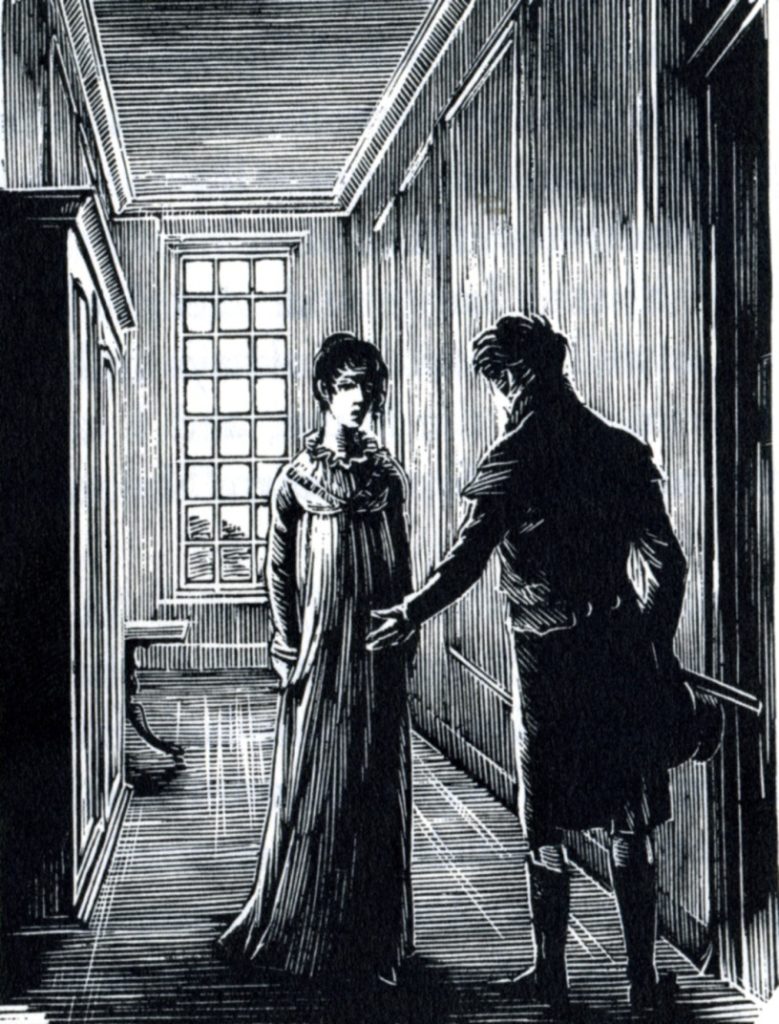

In the 18th century the meaning was expanded to refer to a literary genre whose moody and atmospheric stories were often set amid the ruins of those great Gothic structures, beginning with the Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, published in 1764, which was subtitled “A Gothic Story”. Walpole’s novel was filled with the elements that would come to characterize Gothic literature: a negligee-clad heroine fainting at every plot twist; a gloomy, half-ruined castle; mysteries that smacked of the supernatural; and dark family secrets. Writers such as Mary Shelley (Frankenstein), John Polidori (The Vampyre) and Percy Bysshe Shelley (Zastrozzi) popularized the genre further.

Jane Austen’s novel Northanger Abbey is about a woman who reads so much lurid Gothic fiction that she begins to see murder and mystery behind every cobwebby aspidistra. Austen names the actual books that her character is reading; in the present day there are efforts being made to have them reprinted.

By the middle of the 19th century, the Gothic style had been replaced on the fashionable bookshelf by rollicking historical novels and sunlit tales of adventure and derring-do. Gothic literature persisted, but only in the shadows. Authors such as Edgar Allen Poe (“The Fall of the House of Usher”), Sheridan le Fanu (“Carmilla”, Uncle Silas) and Bram Stoker (Dracula) achieved considerable popularity, but were regarded less as literary figures than as the purveyors of a guilty pleasure. The style eventually degenerated in the 20th century into a sub-genre of the romance novel, with the gloomy castles and busy graveyards serving only as backdrops to the search for True Love.

In the mid-1980s the term was revived to describe a youth sub-culture centered around the “Gothic” literary and artistic themes. The concept did not translate well into music (although a number of heavy-metal bands gave it their best shot) since the “spookiness” that was a part of the Gothic ideal turned popular songs into something that sounded more like movie soundtracks; many musicians, however, took on the dark eye makeup, ghost-white skin, and black clothing that came to characterize the style, and the growing importance of music videos in marketing and popularizing songs meant that the visual style could be as important as the music itself.

Today, blond, blue-eyed Italians still drink coffee in the piazzas of Milan or Bergamo, and elements of Gothic architecture still appear in churches and homes all over the world. Film director Tim Burton has given comic-book antihero Batman the Gothic treatment, and the various forms of Gothic novel are still alive and well. Shoe-black hair and purple lipstick have become so common that Roderick Usher would hardly draw a second glance in the checkout line at Target.

Still, at a time of year when most people are rushing to throw open their windows and let the sun shine in, it has to be hard to keep up the look of someone who has been living in the basement for the last several years. They’re going to an awful lot of trouble, folks: I guess the least we can do is stare.

* * *