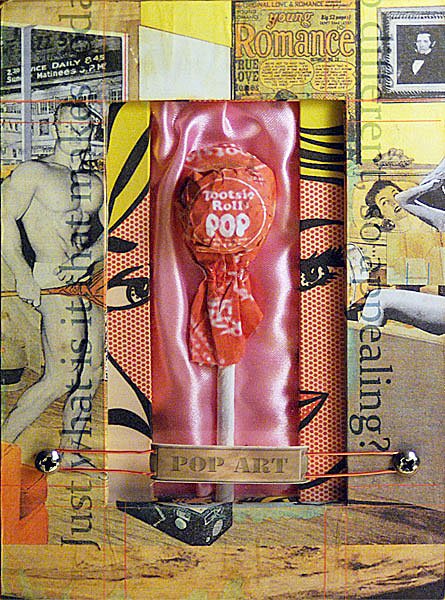

An assemblage of a collage. It may be overkill. (“Pop Art: Homage to Richard Hamilton”, by Dave Holcomb.)

Despite two decades behind a computer (I’m old enough to remember Photoshop 1.0!) I still enjoy getting my hands dirty whenever I can with the kinds of art that don’t involve a mouse and a keyboard.

A big part of the appeal for me of non-digital art is the chemistry of it all: the paints and pigments, chalks and charcoals, glues and glazes. I do a lot of collage and assemblage1, not so much because I feel that I can express myself better with glue and wire than with paint, but because I get to play around with so many different types of stuff.

Tonight I made up a batch of wheat-starch paste. This requires soaking the wheat-starch powder for half an hour or so in water, then cooking it for thirty minutes, very gently, in a double boiler, stirring the whole time. During the course of the cooking, the stuff goes from a pasty white liquid, like watered-down toothpaste, to a translucent, almost pearly, mass, the consistency of cold peanut butter but with the color and texture of alabaster.

I’m using the paste for a project I’m doing that involves gluing a lot of pieces of paper onto a panel: it’s important that the paper not be discolored or damaged by the adhesive, and I need to be able to draw on them after they dry. Pastes made from wheat or rice starch have been used for centuries, and there are illuminated manuscripts and Japanese prints assembled with starch pastes that are as fresh today as they were when they were first executed.

Not all art materials are so benign. Red and yellow paints colored with cadmium salts are believed to have inflicted brain damage on some of the artists who used them. Indian Yellow was produced by boiling down the urine of cattle who had been fed a diet — ultimately fatal for the animal — of nothing but mango leaves. Egyptian Brown was made by soaking a powder of ground-up Egyptian mummies in turpentine and then adding gum arabic or oil. Realgar, a vivid orange pigment, is arsenic sulfide; long-term exposure was deadly. The artist Paul Cezanne suffered from a form of diabetes probably triggered by the use of Paris Green, another arsenic compound.

Toxicity isn’t the only potential risk, there’s also the question of longevity. Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper” was virtually destroyed within only a few years of being completed because of the technique he used, painting on plaster on a damp and mildewed wall. Once of the most distinctive features of Byzantine art is the extensive use of gold leaf and precious stones, which created dazzling effects, but which also made many pieces more valuable disassembled than preserved. Encaustic, in which pigments are dissolved in melted wax, was extremely popular for centuries due to the translucency and brilliance of the colors: unfortunately, a great deal of religious art created using the encaustic technique was damaged or destroyed by the heat and soot of the candles used to illuminate the works.

Oddly enough, the most durable materials tend to be among the simplest. Until the development of an industrial process to make paper out of wood pulp, paper was manufactured from pulverized rags. Rag paper, because of the long and tangled fibers binding it together, and the lack of acids, is incredibly durable and non-yellowing. The pages of books printed in the 17th century often look as fresh today as they did when they first came off the press. Paper made with wood pulp contains tannic acid; also, when wood pulp paper is bleached, sulfuric acid is then used to neutralize the bleach, and rinsed out only imperfectly before the paper is dried. These acids are activated by exposure to moisture and ultraviolet light: put a newspaper outdoors for a week and see what happens.

One of the most effective cleaning materials for antique paintings is human saliva. Very delicate cleaning is often done by the simple expedient of licking a q-tip and rubbing away the dirt. My mother used to clean my face in the car on the way into church by a similar method.

Varnishes and fixatives intended to protect artwork can take their toll. During the latter half of the 19th century, many art collectors believed that a golden-brown haze added to the value of antique paintings: modern restorers have been forced to laboriously clear away layers of murky varnishes and glazes to uncover the original colors of the paintings of artists such as Titian and Caravaggio.

Artists of the 18th and 19th century who specialized in pastel painting, such as Edgar Degas and Odilon Redon, faced the problem of attaching their pigments to the paper: pastel paints are essentially nothing but dry, powdered pigment, with just enough binder to form solid sticks. The particles of color don’t actually stick to the paper, but just lie in the bumps and grooves of the paper’s texture, and will fall out at the slightest provocation. Sprays and varnishes intended to address this problem unfortunately destroy the brilliance of the colors; many of Degas’ great works are now exhibited only in special cases equipped with exhaust systems that gently draw air down onto the paper, preventing the pigment particles from falling off.

Collage is an art technique in which two-dimensional materials such as fabric and paper are used, sometimes in conjunction with paint, sometimes replacing other materials entirely. Assemblage is similar to collage, except that the materials used are three-dimensional, resulting in artwork that is somewhere between a painting and a sculpture.

In collage and assemblage, the problems are somewhat different: the materials are often bits and pieces of things originally intended for other purposes, so their behavior when nailed, glued or wired together can be unpredictable. This unpredictability, of course, is sometimes the whole point. Jean Tinguely’s 1960 work, Homage to New York, was designed to vigorously self-destruct; Joseph Cornell’s shadow boxes are often intended to be shaken up or opened, with some parts being removable so as to be examined more closely.

Me, my expectations are limited: I don’t want my work to disintegrate while it’s hanging on the wall, but I also don’t anticipate the art lovers of 2096 fighting over anything with my name on it. I want things to last long enough to show them to people, and I want to have fun putting them together.

So far as I know, wheat-starch paste and copper wire have never induced anyone to hack off an ear — so far, so good. I’ll keep you posted.

* * *